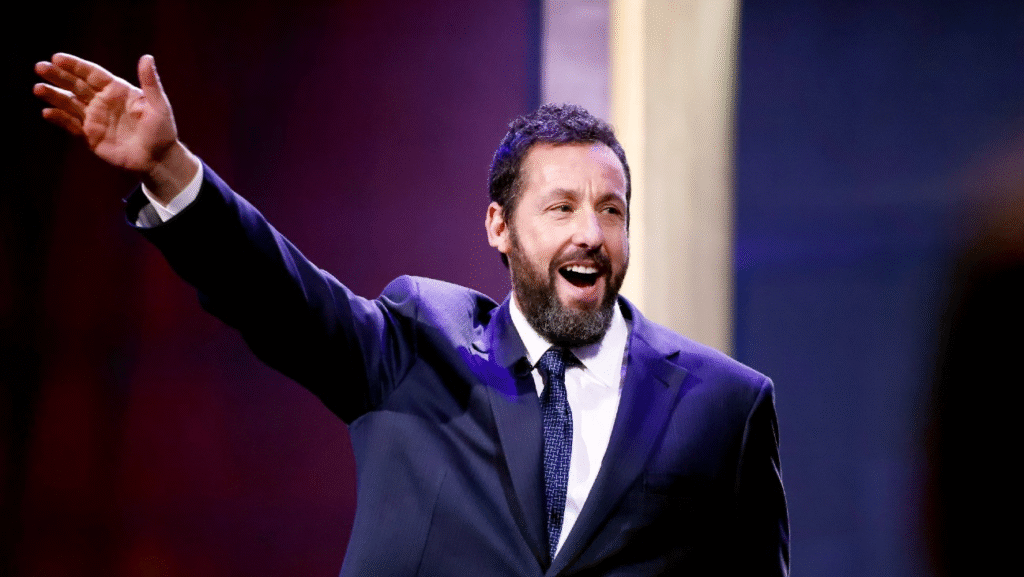

How Adam Sandler Reinvented Comedy

The first Adam Sandler is the one critics love to…

The first Adam Sandler is the one critics love to hate. He’s the architect of films that regularly grace “Worst of the Year” lists. He’s the purveyor of low-brow humor, the king of the fart joke, the man responsible for Rob Schneider shouting “You can do it!” for the dozenth time. This is the Adam Sandler of Jack and Jill, Grown Ups 2, and The Ridiculous 6. To his detractors, he represents the death of sophisticated humor, a lazy, multi-million-dollar enterprise built on recycled gags, apathetic performances, and paid vacations for his friends. The Rotten Tomatoes scores for this Sandler are, to put it mildly, abysmal.

Happy Gilmore 2 | Official Trailer | Netflix

Then, there is the second Adam Sandler. This is the actor who made Paul Thomas Anderson, one of cinema’s most revered auteurs, see a kindred spirit of raw, untapped emotion. This is the man who propelled the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems into a stratosphere of unbearable, heart-pounding tension, earning him the Independent Spirit Award for Best Male Lead. This is the dramatic heavyweight of Punch-Drunk Love, Reign Over Me, The Meyerowitz Stories, and Hustle. This Adam Sandler is hailed as a generational talent, a performer of profound depth, capable of channeling anxiety, grief, and quiet desperation with a startling authenticity that few actors can match.

The fascinating, confounding, and ultimately brilliant truth is that these two figures are not in opposition. They are the same man. They are two sides of the same, incredibly valuable coin. The genius of Adam Sandler isn’t found by celebrating one and dismissing the other; it’s found in understanding how they are inextricably linked.

For over three decades, Adam Sandler has been one of the most dominant forces in entertainment. But his contribution goes far beyond just making a lot of movies. He didn’t just participate in comedy; he fundamentally reinvented it. He rewired the DNA of the comedic protagonist, built a self-sustaining cinematic universe long before Marvel made it a buzzword, pioneered a bulletproof business model that baffled and enraged old Hollywood, and then led the charge for major movie stars into the uncharted territory of streaming.

This is the story of how Adam Sandler, the mumble-singing goofball from Saturday Night Live, became a one-man industry who changed the rules of the game. It’s a story about the creation of a new comedic archetype, the power of a loyal audience, and the surprising art hidden within the chaos. This is how Adam Sandler reinvented comedy.

Chapter 1: The Genesis – Forging a Persona in the Fires of Saturday Night Live

To understand the revolution Adam Sandler would later ignite in cinema, one must first look at the laboratory where his core ingredients were first mixed: Saturday Night Live in the early 1990s. When Sandler joined the cast in 1990, SNL was in the midst of a transition. The “Bad Boys of SNL” era of the late 80s, dominated by the cool, slick personas of Eddie Murphy and the dry, intellectual absurdism of Dennis Miller, was giving way to a new generation. This was the era of Dana Carvey’s masterful impressions, Phil Hartman’s versatile “glue,” and Mike Myers’s meticulously crafted characters like Wayne Campbell and Linda Richman.

Into this landscape of polished performers walked Adam Sandler, a force of raw, unrefined, and deeply weird energy. He wasn’t an impressionist in the traditional sense, nor was he a classic sketch character actor. Sandler’s comedy came from a different place. It was deeply personal, often musical, and unapologetically juvenile. He wasn’t playing a character as much as he was amplifying a specific, bizarre frequency that was uniquely his own.

His breakout moments weren’t slick political commentary or elaborate parodies. They were things like “Opera Man” (Operaman), a character who sang the week’s news in a mock-operatic gibberish. The joke wasn’t sophisticated; it was the sheer, gleeful stupidity of it. He gave us “Canteen Boy,” a naive, perpetually victimized scout who was uncomfortable in his own skin, a precursor to the many misunderstood outcasts he would later perfect.

Most importantly, however, Sandler’s time at SNL established three core pillars of his comedic identity that would define his entire career:

1. The Musical Absurdist: Long before “The Chanukah Song” became a holiday staple, Sandler was using his guitar as a comedic weapon on “Weekend Update.” Songs like “The Thanksgiving Song” and “Red Hooded Sweatshirt” were not technically brilliant compositions. Their charm lay in their rambling, stream-of-consciousness lyrics, his cracking, off-key voice, and the disarming sincerity with which he delivered them. It was anti-comedy in a way. The joke was that this was being presented on national television. This musicality taught Sandler how to connect with an audience directly, creating a sense of intimacy and shared silliness. It was a rejection of the polished, observational stand-up of the Seinfeld era. Sandler wasn’t observing the world; he was inviting you into his own strange, internal one.

2. The Man-Child and His Rage: While characters like Canteen Boy hinted at it, the true Sandler Man-Child persona was bubbling just beneath the surface. It was a character defined by a volatile combination of sweet-natured innocence and sudden, explosive rage. One moment he could be mumbling in a gentle, almost shy voice; the next, he could be screaming with vein-popping intensity. This wasn’t the “cool” anger of Eddie Murphy or the righteous indignation of George Carlin. This was primal, childish, cathartic anger. It was the frustration of someone who couldn’t properly articulate their feelings, so they resorted to screaming. This emotional whiplash would become the engine of his most iconic film roles.

3. The Anti-Cool Aesthetic: In an era of sharp suits and sharper wit, Adam Sandler cultivated an aesthetic of pure slackerdom. The oversized t-shirts, the baggy shorts, the goofy voice—it was all a deliberate move away from the aspirational cool of his predecessors. He wasn’t the guy in the club who was smarter and funnier than everyone else. He was the guy in the basement, drawing weird cartoons and making up dumb songs with his friends. This made him incredibly relatable to a generation of young people who felt more like outsiders than insiders. He wasn’t punching down or punching up; he was just kind of… flailing around.

His infamous firing from SNL in 1995, alongside Chris Farley, was a blessing in disguise. It was the catalyst that forced him to take the persona he had workshopped for five years and build a world around it. SNL had provided the raw materials: the voice, the music, the anger, and the anti-cool. Now, it was time to build the house.

Chapter 2: The Golden Age (1995-1999) – The Rise of the Rage-Fueled Underdog

If SNL was the laboratory, the period from 1995 to 1999 was the big bang. In four short years, Adam Sandler starred in a quartet of films that didn’t just make him a movie star; they laid down a new blueprint for the mainstream comedy film. These films—Billy Madison, Happy Gilmore, The Wedding Singer, and The Waterboy—were the foundational texts of the Sandlerverse.

It was here that he perfected and unleashed his greatest creation: The Sandler Man-Child Protagonist.

Before Adam Sandler, the heroes of mainstream comedies were often guys who were, in some way, “on top of it.” Think of Bill Murray in Ghostbusters or Eddie Murphy in Beverly Hills Cop. They were witty, charming, and usually the smartest people in the room, using their cleverness to navigate a world of idiots. Sandler flipped this on its head. His protagonists were the idiots.

1. Billy Madison (1995): Defining the Archetype

Billy Madison is the Rosetta Stone of Sandler’s comedy. The premise is absurd: a lazy, spoiled, 27-year-old heir must repeat grades 1-12 to prove his competence and inherit his father’s company. The film is a masterclass in regression. Billy is not a witty adult trapped in a kid’s world; he is an actual child in an adult’s body. He speaks in a goofy lisp, makes prank calls, and sees a giant penguin.

But the revolutionary aspect of Billy Madison was its emotional core. Billy isn’t just a moron; he’s a good-hearted moron. The villain, Eric Gordon (Bradley Whitford), is the traditional “smart” guy. He’s articulate, conniving, and condescending. In a classic 80s comedy, a hero like Axel Foley would have outsmarted Eric. Billy Madison out-dumbs him. He wins not by being clever, but by being sincere. The film’s climax isn’t a battle of wits; it’s an “Academic Decathlon” that includes answering a question about literature and then a slapstick sequence involving Mortal Kombat.

This established the first rule of Sandler’s new comedy: Heart over smarts. His characters weren’t aspirational because of their intelligence, but because of their fundamental decency, which always triumphed over the cruelty of the “smarter” bullies.

2. Happy Gilmore (1996): Weaponizing the Rage

If Billy Madison established the Man-Child, Happy Gilmore gave him his defining emotional trait: cathartic rage. Happy is a failed hockey player who discovers he can drive a golf ball 400 yards. He is pure, idiotic id. When he’s frustrated, he screams at a golf ball (“Are you too good for your home?!”), gets into a fistfight with a game show host, and assaults a heckler.

This was a seismic shift. Comedic anger was usually portrayed as a flaw to be overcome. Here, it was a superpower. Happy’s rage is what allows him to hit the ball so far. It’s his defining feature, and the audience is invited to revel in it. For a generation of young men (and women) who felt unheard or frustrated, watching Adam Sandler scream at the universe was deeply cathartic. It was a release valve.

The villain, Shooter McGavin, is, once again, the “establishment” figure. He’s polished, professional, and plays by the rules. Happy is a disruptive force of pure, chaotic energy. The film’s message is clear: sometimes, passion and raw emotion, even when messy and uncontrolled, are more powerful than sterile professionalism. This was the second rule: Passion, in all its chaotic glory, is a virtue.

3. The Wedding Singer (1998): Refining the Heart

The Wedding Singer is often seen as the “sweet” one in the early Sandler canon, and for good reason. Set in the 1980s, it dialed back the overt slapstick and rage (though it’s still there in the iconic “Somebody Kill Me” song) and focused on the romantic core of the Sandler persona. As Robbie Hart, a wedding singer left at the altar, Sandler is at his most vulnerable.

This film proved the Man-Child wasn’t just a one-trick pony. He could be a romantic lead. The key was that he was an unconventional romantic lead. He wasn’t suave like Cary Grant or impossibly handsome like Brad Pitt. He was just a regular, heartbroken guy with a bad haircut. His appeal was his earnestness. When he serenades Julia (Drew Barrymore) on the airplane with the song “Grow Old With You,” it’s not a grand, polished gesture. It’s sweet, a little clumsy, and feels completely genuine.

This film established the crucial third rule: Vulnerability is the ultimate strength. The Sandler hero wins the girl not by being cool, but by being open with his feelings, even the painful ones. This film also marked the beginning of his incredible screen chemistry with Drew Barrymore, a partnership that would ground his comedy in genuine warmth for decades to come.

4. The Waterboy (1998): Perfecting the Formula and Conquering the Box Office

If the previous films were experiments, The Waterboy was the proof of concept, perfected and unleashed upon an unsuspecting box office. The film made over $185 million on a $23 million budget, cementing Adam Sandler as one of the most bankable stars in the world.

Bobby Boucher is the ultimate Sandler protagonist. He combines the childlike innocence of Billy Madison, the explosive rage of Happy Gilmore, and the deep-seated vulnerability of Robbie Hart. He’s a socially inept, 31-year-old waterboy for a college football team, living under the thumb of his overprotective mother. He speaks in a pronounced Cajun accent and believes in the high-quality properties of H2O.

The film is a symphony of all the elements Sandler had developed. The specific, weird voice. The misunderstanding of social cues. The transformation of a personal “flaw” (his pent-up anger from being bullied) into a “tackling fuel” superpower. The triumph of the ultimate underdog over the arrogant, smarter establishment (coaches, professors, rival teams).

The Waterboy demonstrated that the Sandler formula was critic-proof. Reviews were savage, but audiences adored it. Adam Sandler had successfully created a new kind of comedy hero: the Rage-Fueled Underdog with a Heart of Gold. He wasn’t a character you laughed at as much as you laughed with. You cheered for his absurd triumphs because they felt earned, not through wit, but through sheer, unadulterated will and emotion. This was the reinvention. The era of the slick, ironic comedian was over. The era of the screaming, good-hearted Man-Child had begun.

Chapter 3: Building an Empire – The Happy Madison Machine and the “Sandlerverse”

With his A-list status secured, Adam Sandler did something that would prove to be even more revolutionary than his on-screen persona: he took control of the means of production. In 1999, he founded Happy Madison Productions, named after his two earliest hits. This wasn’t just a vanity label; it was the foundation of a comedy empire, a self-sustaining ecosystem that would dominate the genre for the next two decades.

Happy Madison wasn’t in the business of making one-off comedies. It was in the business of producing a specific, branded product. And in doing so, Sandler inadvertently created his own version of a cinematic universe, long before Kevin Feige started mapping out phases for Marvel. Welcome to the “Sandlerverse.”

The Repertory Company and the Comfort of Familiarity

The most recognizable feature of the Sandlerverse is its recurring cast. Watching a Happy Madison film is like attending a high school reunion. You’re guaranteed to see some combination of David Spade, Rob Schneider, Kevin James, Chris Rock, Steve Buscemi, Allen Covert, Peter Dante, and Nick Swardson.

To critics, this looked like cronyism—Sandler just hiring his friends for a paid vacation. And while that may be partially true, its effect on the audience was profound. It created a powerful sense of comfort and familiarity. You knew what you were getting. David Spade would be the sarcastic wise-ass. Rob Schneider would play a bizarre ethnic caricature or an animal. Kevin James would be the lovable, clumsy schlub. Steve Buscemi would show up for a weird and wonderful cameo.

This wasn’t laziness; it was branding. The audience for an Adam Sandler movie wasn’t just coming to see him; they were coming to see the whole troupe. It transformed moviegoing from a single-serving experience into a familiar ritual. This built-in-audience loyalty was the bedrock of the Happy Madison business model.

The Bulletproof Business Formula

The business strategy behind Happy Madison was brutally effective and deceptively simple:

- High-Concept, Low-Stakes Premise: The ideas were easy to explain in a trailer. What if a guy could control his life with a magic remote? (Click). What if two straight firefighters pretended to be a gay couple for benefits? (I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry). What if a group of childhood friends reunited for a weekend? (Grown Ups). The concepts were the hook.

- The Sandler Persona (or a Proxy): Even when Sandler wasn’t the lead (like in The House Bunny or Paul Blart: Mall Cop), the films often featured a Sandler-esque protagonist—a well-meaning but socially awkward underdog.

- The Recurring Cast: The friends were always there, providing the familiar comedic beats.

- The Exotic Location (The “Vacation Movie” Subgenre): Later films like Just Go with It (Hawaii), Blended (Africa), and Murder Mystery (Europe) added a layer of aspirational travel to the formula. The audience got a comedy and a virtual vacation.

- Controlled Budget, Massive Return: Happy Madison films were rarely mega-budget blockbusters. They typically sat in the

40−40-40−80 million range. But they consistently grossed two to three times their budget, especially internationally. Grown Ups cost $80 million and made over $270 million worldwide. Just Go with It cost $80 million and made $215 million.

This model was the bane of the critical establishment. Films like Little Nicky, Mr. Deeds, Anger Management, and 50 First Dates were met with varying degrees of scorn. Critics saw a decline in the energetic creativity of the early films, replaced by a lazier, more formulaic approach. They weren’t wrong. Many of these films are far less inspired than Happy Gilmore.

But the critics missed the point. Adam Sandler wasn’t making movies for them. He was super-serving his massive, loyal, global audience. He understood, perhaps better than any studio executive at the time, that a dedicated fanbase is more valuable than a 90% score on Rotten Tomatoes. While other studios were chasing trends and trying to please everyone, Sandler was doubling down on his brand. He gave his audience exactly what they wanted, time and time again, and they rewarded him with unwavering loyalty and billions of dollars in ticket sales.

The Happy Madison machine wasn’t just reinventing the content of comedy; it was reinventing the business of it. It was a closed-loop system where the star was also the producer, the brand, and the chief architect of a universe his fans never wanted to leave. This industrialization of his own persona was, in its own way, a work of genius.

Chapter 4: The Pivot – The Surprising Art of a Serious Adam Sandler

Just as the world was ready to permanently label Adam Sandler as a low-brow schlockmeister, something strange happened. In 2002, he starred in Punch-Drunk Love, a film by Paul Thomas Anderson, the celebrated director of Boogie Nights and Magnolia. The announcement was met with bewilderment and derision. What could a serious artist like PTA possibly see in the guy who made Little Nicky?

The answer was: everything.

PTA didn’t ask Sandler to suppress his signature traits; he asked him to channel them into a different context. This decision would spark a parallel career for Sandler, a “prestige track” that would run alongside his mainstream comedies and reveal the profound artistic depth lurking within the Man-Child persona.

1. Punch-Drunk Love (2002): Deconstructing the Sandler Rage

In Punch-Drunk Love, Adam Sandler plays Barry Egan, a lonely novelty plunger salesman with crippling social anxiety and seven overbearing sisters. He is prone to sudden, violent outbursts. Sound familiar? Barry Egan is a Sandler protagonist. He is Billy Madison, Happy Gilmore, and Bobby Boucher, but stripped of the comedic fantasy and placed in the harsh reality of the San Fernando Valley.

PTA saw that the rage in Happy Gilmore wasn’t just a gag; it was a manifestation of profound emotional distress. He took that same energy—the screaming, the destruction of property (in this case, a glass door), the awkward mumble—and treated it not as a joke, but as a symptom of a wounded soul. The film is a romantic comedy, but it’s also a deeply empathetic portrait of anxiety. Sandler’s performance is a revelation. He’s not “acting” differently; he’s just directing the same raw energy toward drama instead of slapstick. The film legitimized him in the eyes of the cinephile community and earned him a Golden Globe nomination. It proved that the very things critics mocked in his comedies were, in fact, the source of his dramatic power.

2. The Interim Years: Reign Over Me and The Meyerowitz Stories

Sandler would periodically return to this dramatic well. In Reign Over Me (2007), he played a man shattered by the loss of his family on 9/11. It was a more traditional dramatic role, showcasing a quieter, more sustained grief. While the film itself received mixed reviews, Sandler’s performance was widely praised for its raw, heartbreaking sorrow.

A decade later, he collaborated with another indie darling, Noah Baumbach, for The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) (2017). Here, he played Danny Meyerowitz, the overlooked son of a narcissistic artist (Dustin Hoffman). This was a different kind of performance yet again—less about explosive rage and more about the simmering resentment and disappointment of a life lived in a father’s shadow. His physicality—the limp, the slumped shoulders—spoke volumes. Sharing the screen with legends like Hoffman and accomplished actors like Ben Stiller, Sandler more than held his own, delivering a performance of subtle, nuanced pain.

3. Uncut Gems (2019): Weaponizing the Sandler Anxiety

If Punch-Drunk Love deconstructed the Sandler persona, the Safdie Brothers’ Uncut Gems weaponized it. As Howard Ratner, a gambling-addicted New York City jeweler, Sandler delivered the performance of his career. The film is a two-hour-and-fifteen-minute anxiety attack, and Sandler is its relentless engine.

The Safdies did something brilliant. They took every hyperactive, chaotic, and loud element of Sandler’s comedic brand and dialed it up to 1000, but in the context of a high-stakes thriller. Howard is constantly yelling, scheming, and making terrible decisions. He has the delusional self-belief of Happy Gilmore and the desperate energy of a cornered animal. It’s a performance of pure, uncut chaos.

What makes it so masterful is that it feels like the ultimate culmination of his entire career. The fast-talking hucksterism, the misplaced optimism, the belief that one big score will solve everything—it’s all there. But here, the stakes are life and death. The film was a critical sensation, and while Sandler was famously snubbed for an Oscar nomination, he won the Independent Spirit Award and cemented his status as one of the most compelling and unpredictable actors of his generation.

4. Hustle (2022): The Mature Mentor

His most recent dramatic turn in Hustle shows yet another evolution. As Stanley Sugerman, a weary basketball scout, Sandler is no longer the Man-Child. He’s the mentor. He’s channeled the passion and rage of his youth into a world-weary but fiercely protective love for the game and his discovery, Bo Cruz. It’s a warm, soulful, and deeply winning performance. It feels like the natural, mature endpoint for the Sandler protagonist—he’s finally grown up, but he hasn’t lost the fire that made him special.

This dramatic pivot is not a separate career; it’s the other half of the reinvention. It proved that his comedic instincts were rooted in a deep well of genuine emotion. The directors who “got” him understood that you don’t tame Adam Sandler; you aim him. By doing so, they revealed the art that was always there, hiding in plain sight behind the goofy voices and the slapstick.

Chapter 5: The Streaming Revolution – How Adam Sandler Conquered Netflix and Changed Hollywood Forever

By the early 2010s, the theatrical comedy was in trouble. The reliable profits of the Happy Madison model were beginning to wane as audiences’ viewing habits shifted. The mid-budget movie, Sandler’s bread and butter, was being squeezed out by superhero blockbusters and low-budget horror. For any other star of his generation, this would have signaled a slow decline into irrelevance.

But Adam Sandler, ever the disruptor, made a move that was as bold as it was baffling to the old guard of Hollywood. He didn’t just adapt to the new digital landscape; he became one of its founding fathers.

In October 2014, Netflix announced it had signed Adam Sandler to an exclusive four-movie deal for a rumored $250 million. The industry was stunned. At the time, Netflix was still primarily known for licensing old content and producing a handful of prestige TV series like House of Cards. A-list movie stars did not simply bypass the entire theatrical studio system to make movies directly for a streaming service. It was seen as a step down, a move of desperation.

The Hollywood establishment laughed. Pundits predicted failure. They could not have been more wrong. Adam Sandler had once again reinvented the game.

The Netflix Era: Critic-Proof on a Global Scale

The first films from the deal, The Ridiculous 6 (2015) and The Do-Over (2016), were met with some of the worst reviews of Sandler’s entire career. The Ridiculous 6 holds a staggering 0% on Rotten Tomatoes. By traditional metrics, the deal was a catastrophe.

But Netflix released a different kind of metric: viewing hours.

In early 2017, Netflix revealed that subscribers had spent more than half a billion hours watching Adam Sandler movies since the release of The Ridiculous 6. The company called his films some of their most successful original investments. They promptly re-upped his deal for four more movies.

What Sandler and Netflix understood, and what old Hollywood failed to grasp, was that the rules of success had changed. In the streaming world, the only metric that matters is engagement. A subscriber doesn’t care about a Tomatometer score when they’re scrolling for something to watch on a Friday night. They care about comfort, familiarity, and ease of access.

The Adam Sandler brand was perfectly engineered for the streaming age. His movies are the ultimate “comfort food” cinema. You know exactly what you’re going to get. They are easy to watch, undemanding, and feature a cast of familiar faces. For a global audience, the broad, physical humor and simple emotional stories translated perfectly, unhindered by cultural or linguistic barriers.

From Murder Mystery to Global Franchise

The crowning achievement of the Netflix era is arguably Murder Mystery (2019). Co-starring Jennifer Aniston, the film was a breezy, fun, and slickly produced genre-mashup that perfectly leveraged Sandler’s “everyman” persona. He’s no James Bond; he’s a New York cop on a European vacation who gets in over his head.

Netflix reported that the film was viewed by nearly 31 million households in its first three days, one of the biggest opening weekends for any film, streaming or theatrical, that year. It became a genuine global phenomenon, spawning a successful sequel, Murder Mystery 2 (2023), and establishing a new, viable franchise for both Sandler and the platform.

Sandler’s move to Netflix was a paradigm shift for the entire industry. He proved that:

- A-List Stars Could Thrive Outside the Studio System: He paved the way for other major stars like Ryan Reynolds, Dwayne Johnson, and Leonardo DiCaprio to sign lucrative deals with streaming platforms.

- A Loyal Fanbase is the Most Valuable Currency: In the age of algorithmic content, a built-in, loyal audience is more powerful than marketing spend or critical acclaim. Sandler had spent two decades building that audience, and he cashed in spectacularly.

- The “Movie” Itself Was Redefined: A “movie” was no longer just something you saw in a dark theater. It was content to be consumed anytime, anywhere. Sandler’s films were perfectly suited for this new, more casual viewing experience.

He didn’t just join the streaming revolution; he helped lead it. By taking his brand directly to the consumer, Adam Sandler once again bypassed the gatekeepers and rewrote the rules of what it means to be a movie star in the 21st century.

Chapter 6: The Sandler Legacy – More Than Just a Goofy Voice

So, what is the ultimate legacy of Adam Sandler? How will he be remembered? Is he the critically-maligned king of schlock, or the secretly brilliant dramatic actor?

The answer, as we’ve seen, is that he is both, and the greatness lies in that contradiction. His legacy is one of profound and multifaceted reinvention.

He reinvented the comedic protagonist. He replaced the slick, smart-mouthed hero with the emotionally volatile, good-hearted Man-Child. The Sandler hero—from Billy Madison to Stanley Sugerman—is a triumph of heart over intellect, of raw passion over polished professionalism. This archetype has influenced a generation of comedy, paving the way for the lovable slackers of the Judd Apatow universe (Seth Rogen, Jason Segel) and the absurd musicality of The Lonely Island (who are, fittingly, fellow SNL alumni).

He reinvented the business of comedy. With Happy Madison, he created a self-sustaining comedy factory, a “Sandlerverse” built on a recurring cast, a familiar tone, and a bulletproof financial model. He treated his own persona as a brand and, by super-serving his fanbase, built an empire that was impervious to critical scorn. He understood his audience better than any studio did, and he leveraged that understanding into unprecedented power and control over his own career.

He reinvented the movie star’s relationship with distribution. His landmark Netflix deal was a seismic event that shattered the theatrical-first model and heralded the dominance of streaming. He proved that a global superstar could not only survive but thrive by going directly to the audience, changing the calculus for every major actor, director, and studio in Hollywood.

And finally, he has repeatedly reinvented himself. The periodic, shocking pivots to drama are not an aberration; they are an essential part of the Sandler story. They reveal the artistic truth that was always present in his comedy: that the rage, the anxiety, and the vulnerability were never just a joke. They were real. Acclaimed directors like PTA, Baumbach, and the Safdies simply provided a different lens through which to see the art that his fans had felt all along. The man who gave us Uncut Gems is the same man who gave us Happy Gilmore. The brilliance is not that he can do both; it’s that both come from the same authentic, chaotic, and deeply human place.

Adam Sandler’s career is a paradox. It’s a testament to the power of ignoring the critics and trusting your audience. It’s a story of how low-brow humor and high art can spring from the same creative well. He is an auteur of the absurd, a mogul of the mainstream, and a surprisingly complex dramatic force.

For decades, the question has been: “Is Adam Sandler good or bad?” It’s the wrong question. The right question is: “What did Adam Sandler change?” And the answer is: just about everything.